Notes on Drawing Mantis Dicks

Anatomically Correct Bugfucking is in a dire state.

This may be the least accesible page on this site; the intersection of prurient interest and autistic hyperfixation targets a narrow band indeed, and you need be a deep level of fetishism to even comprehend the problem we’re here to solve.

Really, I’m writing this page half as reference for my future self, because I worked hard to understand this shit, and it’s too arcane to trust unaided memory.

Motivation

Skip this if bug sex needs no justification →

If you’re familiar with furry porn, then you’re familiar with knots. Canines come with a bulb of erectile tissue that inflates at the climax of copulation, “tying” the male to the female for a period, aiding reproductive success.

This is well understood in the furry fandom, and it’s difficult to overstate its influence. It’s not a mere fun fact, or a inert bit of anatomy you’re expected to reproduce to draw “on-model” characters (although it is both of those things). Knotting alters the narrative structure of sex scenes involving canine characters, with the act of “knotting” being a major scene beat on par with first insertion or climax. Attention to this bit of physiology offers novel artistic and storytelling possibilities.

It’s not just flavor, it’s xenofiction.

And the fandom has latched onto it hard. Furries will add knots to anything — I’ve seen more knotted dragons than non.

But knots are merely the most well-known, and emphatically not the only novel twist on sex to be found in the animal kingdom. But the only bit of animal anatomy remotely as popularly understood is hyena’s pseudopenis, and even that mainly manifests as justification to draw hyena-morphs as disproportionately transfeminine (or gynomorph, if you must). Actual pseudopenes, let alone anatomically correct hyena mating, is a rare thing.

Snakes have mating plugs, mating balls, and evocative lock and key genital structure. Most birds engage in cloacal kissing rather than penetration. And these are just easily recognizable animals — remember, this is a whole kingdom.

But if there’s one thing that defines the furry fandom, it’s almost power-law distribution to what species it focuses on. If you like anatomically correct canines, you will feast. But such education is vanishingly rare for other species.

I’d argue there’s almost network effect to it. Not all canines have knots, but a species a tenth as popular doesn’t get proportional attention to detail; technical accuracy becomes multiplicatively rare.

Do you know what’s the most underserved niche in the furry fandom?

Probably microscopic organisms (I’ve only seen a Hydractinia echinata-morph once), but insects are inarguably barren compared to the mammals, avians, or herptiles. Enough that a fan of insects is eating good if a piece of art even looks like a bug. Accuracy? Forget about it.

But believe it or not, this isn’t laziness on part of the fault of the artists. Artists are lazy, no doubt about it (when was the last time you encountered anatomical genitalia other than canine or equine penes?), but if an artist tries to learn?

Actually, you can prove this for yourself. Stop reading this article. Go, try to find out what a mantis penis looks like.

When you give up, go try to find out what any bug penis looks like.

It’s legitimately difficult. Part of this is physics — you require specialized equipment to capture these literally microscopic structures. Part of this is lack of interest. Studying insect genitalia is a niche of a niche of a niche. There’s just not that much literature to even pursue.

But worse than that, the literature sucks.

Imagine you are a space alien, and want to learn about these creatures from another planet called humans. You want to draw a human, and humans have faces, right? So how do you draw a human face? The head has two parts: the skull, attached to the lower jaw.

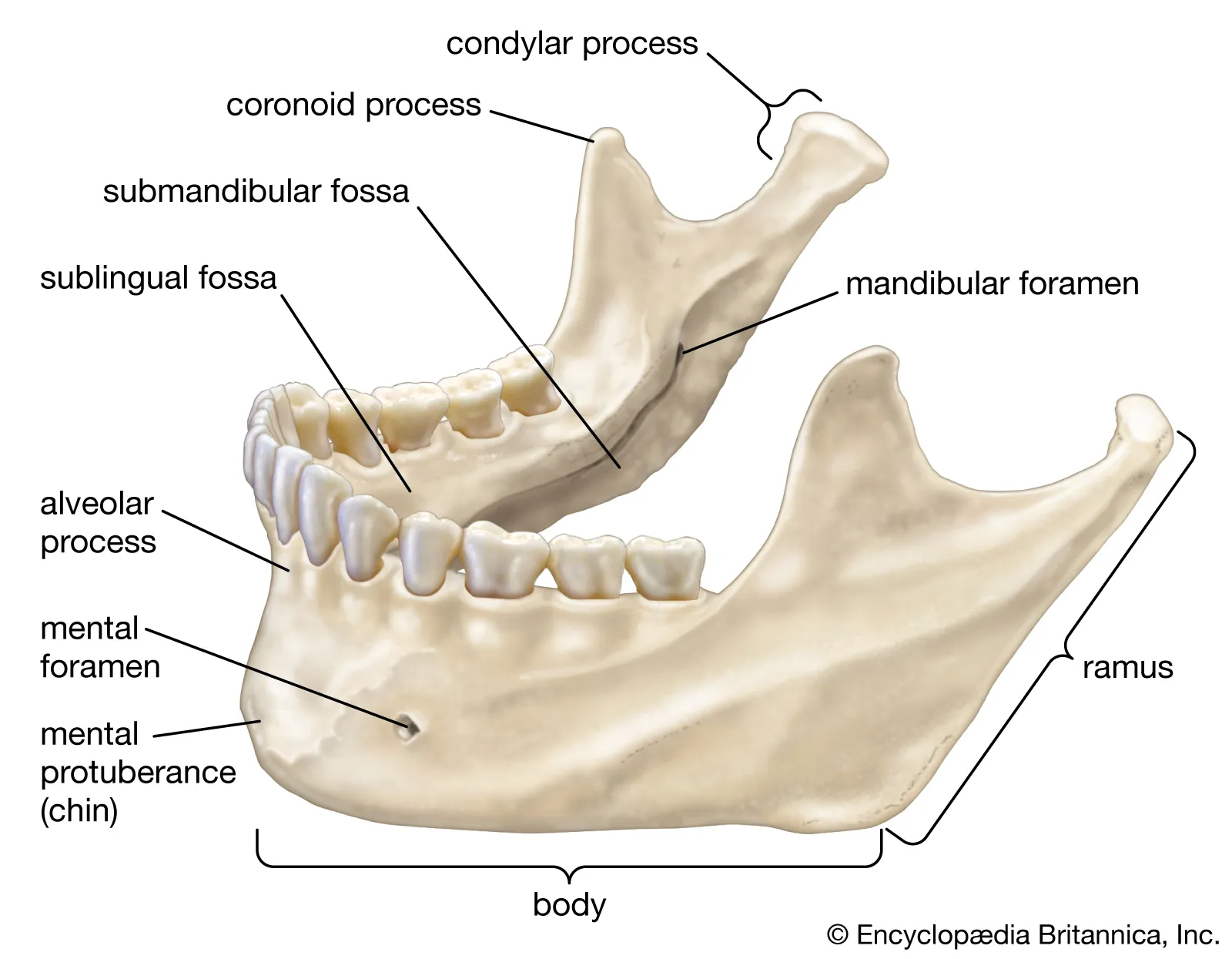

You look up what a lower jaw looks like, and you find half a dozen papers, and they have diagrams like this.

Or like this:

And like, okay. That’s… kind of helpful? It lets you draw a jaw in a vacuum but… how does it attach to the head? What does a head look like?

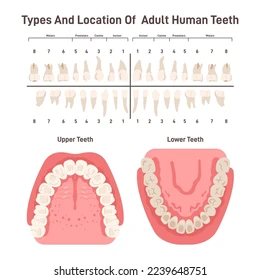

Imagine you try to find a photo of a real human, and it’s all satellite shots like this:

(If you listen closely, you can still hear my scream of frustation echoing.)

But it gets worse.

What if you wanted to learn mantis anatomy, and nobody could agree what the bits are even called? Is it an aedaegus, or male genitalia, or terminalia? What if one paper starts talking about the hypophallus and you have to consults a random godamn pdf which translates between ten (10) different schemes for male genitalia terminology. This is how you discover hypophallus means the proximal mesal process of left phallomere. Or as his friends call him, posteromesal (left phallomere). (Also known as Membranous evagination, though the best paper of the lot labels it as “membranous lobe with sclerotized protuberance.”)

(My scream still echoes.)

But I can only rant (and you can only stand reading) about the state of the literature for so long.

I eventually waded through enough of these papers, and it finally clicked, and I knew bugfucker enlightenment, at least for the very specific issue of typical male mantis genitalia.

My primary source for this post is “Unique set of copulatory organs in mantises: Concealed female genital opening and extremely asymmetric male genitalia”, (henceforth referred to as Hashimoto (2016)). This paper has a dry and mildly convoluted exposition, but the first actual explanation of copulation, and several illustrative diagrams.

It’s a short (~8 pages) and decently readable paper, and most of this blog post is an exegesis of information contained there. It’s worth checking out even if academic jargon scares you — I don’t steal all its diagram, so anyone serious about drawing lewd mantes would be missing out.

If you take away nothing else, know that the key to understanding anatomy is physiology — i.e., what things are actually for. Is it easier to remember (and badly reproduce) the dozens of contours of the human hand, or to understand that we have a thumb and four fingers, with three joints per finger? Knowledge means compression.

More importantly, this is the sort of thing you need to get in order to stylize a hand. The more important part of a hand is that it has fingers, rather than (say) the bump that exists around the knuckles. Even the number of fingers isn’t even that important as long as you get the gesture and relationships right.

If you want to stylize and exagerrate insect dicks (why else would you sit through all of this?), you need to know how insects fuck.

How It Works

So, here’s my plain english take on how the fucking happens.

You know how insects have mouthparts? Instead of one clean opening, there’s a bunch of hairy fingery things with various functions? (I should probably write an article on mouthparts, that would be much more broadly useful.)

While, by that same token, mantids, at least, also have fuckparts.

Male mantids. Sources: Photo by Henrique Rodrigues (top), From Tom Fuschia (left) From Robin Lee (middle right), Alvesgaspar (bottom right)

You can think of a male butt at rest as like a closed mouth. All of his parts are stowed away inside. Pay attention to the cerci, the pair of feelers sticking out of the end of the abdomen. These are important landmarks for orienting yourself when we look at zoomed in photos.

Now, when it’s time for action and the bits come out, it looks like this:

That’s a bit to take in. Though believe me, there are scarier diagrams.

(There’s something deeply amusing to note, if you look closely. Like all bilaterians, insects develop paired structures. Can you find the pairs in that image? That’s right. Past all of the layers of obfuscation, mantid genitalia isn’t even symmetrical! The madness has depths…)

Anyway, we can simplify this down to three parts. Hashimoto (2016) called them DLC (dorsal left complex), VLC (ventral left complex), and RP (right phallomere). But we’re going to create the torment nexus, and frankenstein our own bespoke terminology. For the most part, I think I’m going to go with the terminology used in “Phylogeny and evolution of male genitalia within the praying mantis genus Tenodera (Mantodea: Mantidae)”, which will be confusing since it’s the odd one out of the three sources I cite. (Why am I using it anyway? I’d rather say hypophallus than circumlocate the left phallus’s proximawhatever the fuck, and I think it’s simply human nature to want to use the word “titillator” and yet be technically impeccable.)

I’m going to call DLC the left epiphallus, RP the right epiphallus, and to VLC I grant the honor of being the aedeagus.

Here’s some more images showing what these individual bits look like. I could edit the text in these to be consistent with our terminology, but I was also planning to do example drawings for more than just the first image and I’m too tired to do either of those things. Be happy there’s an article at all, or bug me about it later.

But what do they do? In short, the epiphalli help pry open the female genitalia, and the aedeagus delivers the spermaphore (i.e. it cums).

Specifically, the left epiphallus bears the titilator, which hooks onto the edge of the female’s genitala sheath. A v-shaped groove along the right epiphallus, the acutolobus, grasps the ovipositor. Because the male’s terminalia meets the female’s at an angle, by pulling the left and right epiphalli apart, the female’s inner cavity is exposed. Through a duct in the aedeagus’s hypophallus, the act is concluded.

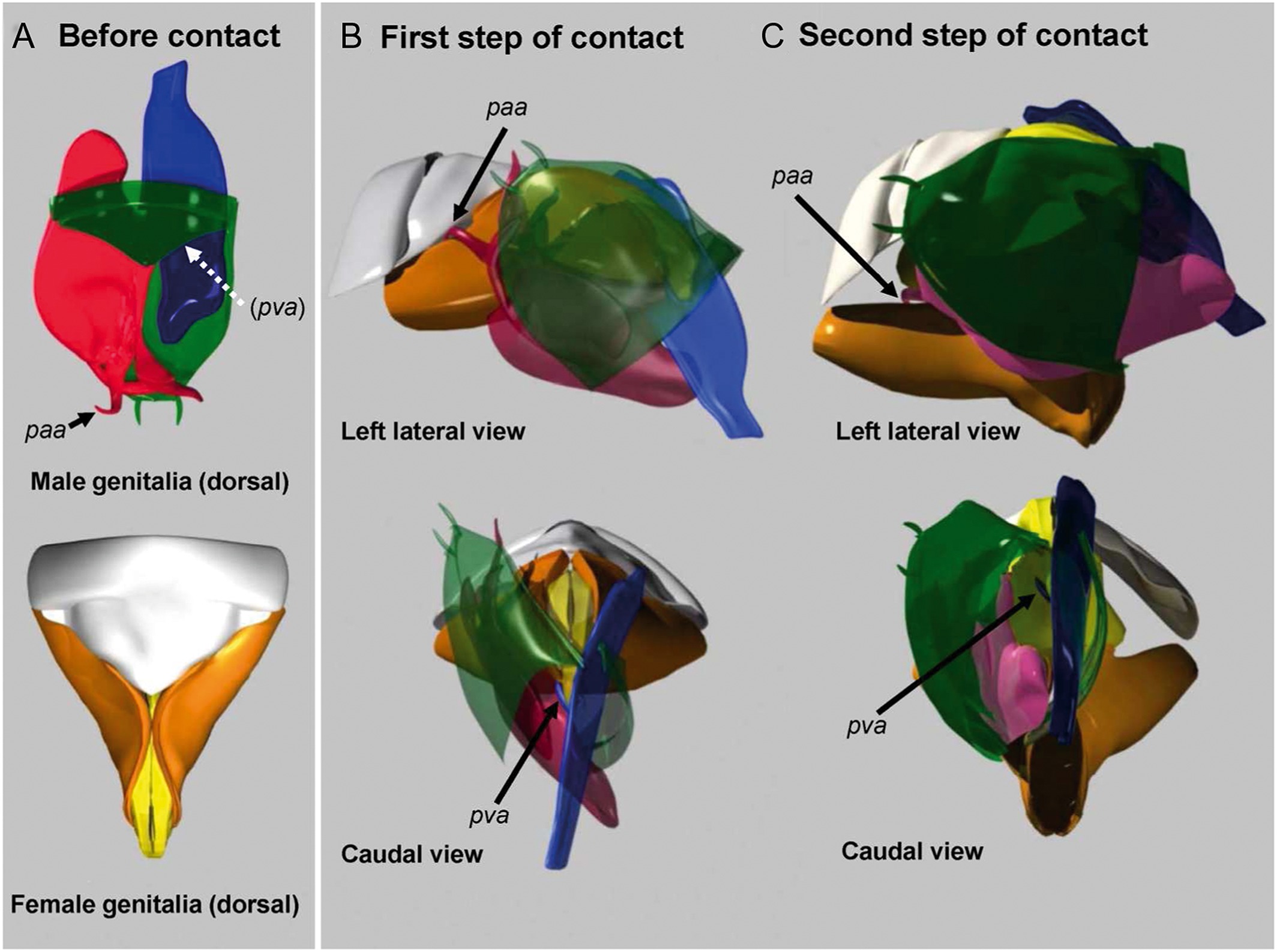

Hashimoto (2016) has a remarkable diagram which lays this all out clearly:

My explanation, though clear, may be too concise. Let me quote the exposition from that paper at length:

It is usually difficult to directly observe mating sequences because some occur very quickly. The results from experiments using surgical treatments and attachment of fluorescent beads suggest that paa is essential for males to open the female genitalia and pda has a significant function in depositing a spermatophore. Based on these results, the 3D model was constructed (Appendix S1). This model predicted the sequences of male and female genital coupling. If the paa of the male DLC hooks the edge of the left side of the female sgp when the male is searching this edge with the paa around here, the pva of the male V-shaped cleft of RP is positioned at the ventral side of female ovi (Fig. 3B). In this situation, the lever force of the male abdominal twist seemed to result in lifting of the female ovi from its sheath sgp (Fig. 3C). Thus, the female gonopore may be exposed to the male. The pia, forming the V-shaped cleft with the pva, and the afa, close to the pva, may also contribute to lifting the female ovi. After that, the male inserted the VLC into the cavity of the female sgp, adjusting and keeping it at the appropriate position within the sgp by pda. If the spermatophore is attached, the male withdraws his genitalia. Thus, hooking of the male paa at the edge of the female sgp is the most important step to begin copulation.

Have a few more diagrams:

One last attempt to explain it simplest of all: the left bit hooks onto the bottom, the right bit grips onto the hood to pop it open, and the middle bit is the dick proper. If you were writing about this casually, you could do worse than talking about a hook, a gripper and whatever your preferred word for ‘dick’ at that moment is.

As I stared at this diagrams for a while, I pushed the pieces into place, and I finally understood.

When it did, I grew rather disappointed that this understanding (in the context of furry porn) is quite possibly nearly unique. I wouldn’t call it the most interesting reproduction mechanism, but it is undeniably interesting.

First of all, instead of simply sticking part A into slot B, there’s an element of positioning and angling. I’ll make some choice quotes from Hashimoto (2016):

According to a review by Maxwell (1999), females can raise their abdomens to prevent intromission and might keep their ovipositor shut to lock out suitors. The male hook-like genital processes suggest they could play a role in coercive copulation, but this assumption has not been tested.

This seem fruitful territory for a comic or smut. Imagine an entire sequence of playful maneuvering as foreplay — one could easily analogize it to kissing.

Also, consider this amusing observation:

In Ciulfina species, males with both genital orientations can mate with the same female (Holwell & Herberstein 2010). Holwell et al. (2015) demonstrated that there are no functional differences between sinistral and dextral genitalia, and both morphs have equal levels of mating success.

Not only is the possibility of “lefty” and “righty” males cute, but the ambiguous phrasing almost suggests both could mate at the same time (is that what’s going on in this amusing photograph?).

The paper doesn’t demonstrate this, but this feels like cute gag:

Little information is available about insect’s learning of sexual behavior. From a traditional viewpoint, there has been little opportunity for insects to learn about courtship and mating, as their life spans are so short. However, a recent study demonstrated the importance of plasticity of insect mating behavior (Dukas 2006). If this applies to mantises, males might learn successful mating techniques by repeated trials of left- and right-ward abdominal twisting, and unmated males are predicted to take more time to copulate than those with mating experience. In our study of T. ardifolia, however, mating experience did not affect mating behavior, either in the direction of abdominal twisting or in precopulatory or copulation duration. In fact, we could not observe any trial-and-error process by the virgin males mounted on the females.

A whole new dimension of missing the hole.

And so on

Hopefully you found that inspiring. Or maybe I just ruined mantis porn for you — oh who am I kidding, not like there was any to begin with.

// todo: add sources for all the images; draw illustrations from the reference material

// summarzie it all in an infographic people can link around?